What President Made Thanksgiving a Holiday? A Story of Politics and Pie

Before it became a holiday, Thanksgiving was absolute chaos. The president who changed that had more on his plate than just turkey and pie.

Published Nov. 21 2025, 3:56 p.m. ET

Americans have been celebrating Thanksgiving in one form or another since long before the days of televised parades and canned cranberry sauce. Today, it’s a comforting mix of gratitude, gravy, and group texts about who's bringing what.

The road to making it a national holiday was anything but smooth. In fact, the story behind what president made Thanksgiving a holiday includes decades of public pressure, regional disputes, and one woman’s relentless letter-writing campaign — all culminating in a moment of unity during one of the darkest chapters in American history.

And yes, there was pie — just not in the way you’d expect.

What president made Thanksgiving a holiday? The story is more complicated than you think.

Thanksgiving wasn’t always set in stone. Long before a national holiday existed, Americans celebrated it in wildly different ways. Some states observed it in October, others in December. Southern states mostly ignored it altogether. And while presidents like George Washington and James Madison had issued one-time proclamations of thanksgiving, the idea of a permanent national day of gratitude remained just that — an idea.

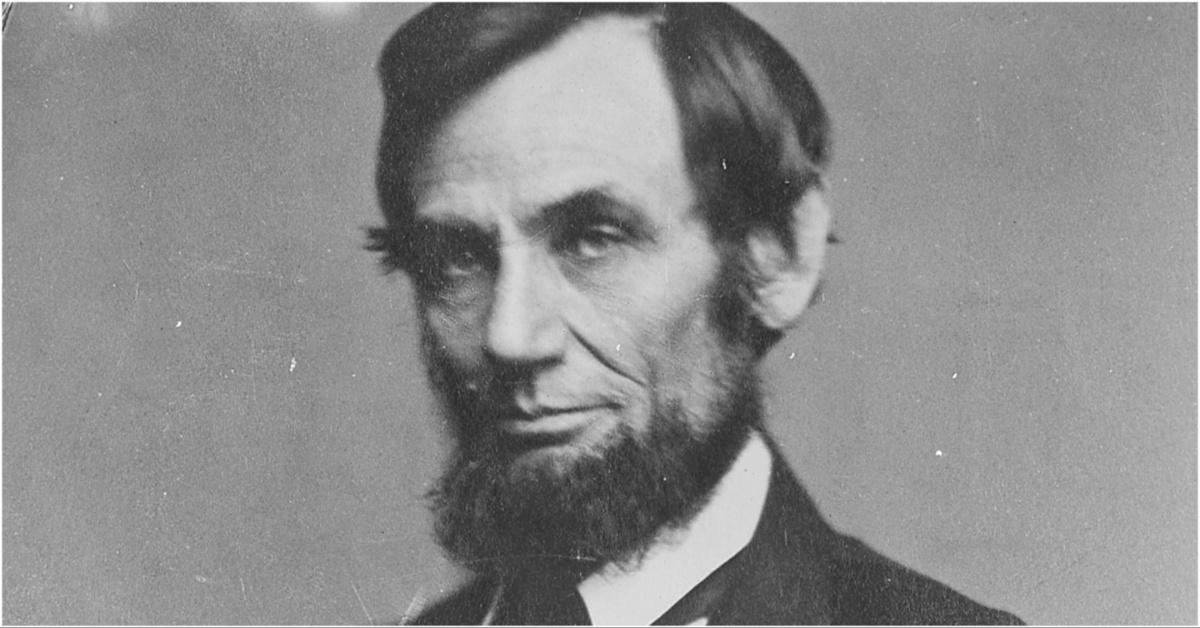

According to the National Archives, it was President Abraham Lincoln who made Thanksgiving an official, recurring national holiday, but he didn’t do it alone. In 1863, in the midst of the Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln issued a proclamation designating the last Thursday in November as a national day of “Thanksgiving and Praise.” His goal wasn’t just to establish a tradition; it was to help bring a fractured nation back together.

The proclamation was a direct response to the tireless campaigning of Sarah Josepha Hale, a magazine editor best known for writing Mary Had a Little Lamb. For 17 years, according to the National Park Service, Sarah had written editorials, published Thanksgiving recipes, and lobbied five presidents to formalize the holiday.

Her appeal to President Abraham Lincoln, written in the summer of 1863, landed at just the right time. Months after the Battle of Gettysburg, the nation was reeling, and her vision of a unifying, peaceful tradition found its moment.

Thanksgiving had been celebrated locally before — particularly in New England — but President Abraham Lincoln was the first to make it national and consistent. His proclamation gave it structure and legitimacy. Northern states quickly adopted the observance. Southern states would follow after the war ended.

The date didn’t always stick, and neither did the peace.

Fun fact: The first federal Thanksgiving wasn’t actually about turkey. When George Washington declared a day of thanksgiving in 1789, it was more about civic gratitude than stuffing. In fact, even the famous 1621 “First Thanksgiving” likely featured venison, corn, and shellfish — not pumpkin pie or mashed potatoes, according to research from the Smithsonian Magazine.

Even after President Abraham Lincoln’s proclamation, Thanksgiving’s date wasn’t entirely locked in. In 1939, President Franklin D. Roosevelt moved the holiday up a week to boost retail sales during the Great Depression.

Critics dubbed it “Franksgiving,” and the backlash was so intense that for two years, Americans celebrated Thanksgiving on two different dates depending on where they lived. Congress finally intervened in 1941, making Thanksgiving a legal federal holiday set for the fourth Thursday in November, where it remains today.

The next time someone passes you the gravy on Thanksgiving, remember: it took a civil war, a poem-writing editor, and a president known for solemn speeches to make that moment possible.